- Home

- Courtney Collins

The Untold Page 19

The Untold Read online

Page 19

You got her? said the postmaster.

Barlow did not reply.

Are you ready to be a hero, Sergeant?

I think it is too late for that, said Barlow.

BARLOW RODE UNDER THE STARS as a man unafraid of death. Riding up Old Road, he felt, at last, like he was a light himself.

When he entered the hut, he did not bother to spark up a lantern. He could see well enough that the place had been trashed. He knew where there was rope and he was grateful that the rope alone had not been disturbed.

He walked out to the tree in front of the hut and threw the rope around its thickest branch. And then, holding tight to the rope, he climbed up the trunk of the tree. He perched in the V of the branch and tied the rope around his ankles. Then he threw himself back. The loops in the rope tightened around his legs and spun him, around and around, beneath the tree.

He was conscious enough to reflect that if he had hung himself by his neck his death would have surely come faster. But this was the way he chose, to give himself slowly over to gravity, vertebra by vertebra. It was his own death and he did not fear it.

Jack Brown and Jessie rode up the widening track to the house. When they reached the back entrance, Jack Brown swung down from his horse. The kitchen door was open and the madam burst out.

Jack! We’ve missed you! When are you going to give up your post at the policeman’s hut and come join us here for good?

Jack Brown walked towards the madam.

Hold up, she said. Don’t come any closer. You smell like a fucking trooper yourself. You need a wash and a good feed. And by the looks of her, so does your friend.

What I need is a favor, said Jack Brown. I need a safe place to hide Jessie for the night. There’s a few rough men out to get her.

And us all! The madam laughed. She’ll be right as rain. Is Lay Ping expecting you tonight?

No.

She’ll be real glad you’re here, Jack Brown. You’re all that we hear about these days.

The madam set Jessie up in a room and gave her a silk robe for the evening and a skirt and a cotton blouse to change into in the morning. Jessie washed herself in the basin and put on the robe, which felt like cold water against her skin. She lay back on the four-poster bed with its flounces and embroidered flowers. A room like this was so foreign to her.

That night she did not sleep. She stared up at the canopy of the bed. With candles burning on wooden chests on each side of it, the room cast its own moving shadows upon the canopy. She saw there a boy on a trapeze, his shadow moving along the roof of a circus tent. And just as she had seen happen so many years before, there he was, stepping out across the rope and falling.

When she closed her eyes she saw herself hovering over the place where he landed. She could see her own hands stroking the dust where his limbs had fanned out, where his fingers had made trails.

When the constabulary arrived the next day, Jessie was sitting on the veranda of the homestead, her feet cuffed together. She was wearing a style of dress she had never worn. The cotton blouse the madam had given her had a ruffle on each shoulder and the skirt fanned out in pleats. Before the sun was up, she had dressed and combed out her hair from its tangle of knots. All kinds of leaf matter had rained around her, and it was the only thing left of her in the Seven Sisters because she had fed her own clothes to the fire.

Jack Brown sat beside her.

They sat in silence and watched the six members of the constabulary beating a track towards them, tall in their saddles with a spare horse between them.

Fuck, Jessie, said Jack Brown. Why didn’t you escape?

I’m not dead yet, Jack Brown, she said and there was a grin on her face that Jack Brown had not seen for a very long time.

Thanks for the hat, she said. Does it suit me?

It’s dangerous out there now, Jessie. Everybody wants a piece of you.

When the officers arrived they did not regard Jack Brown. They just lined themselves up in front of my mother and one of them said, Are you Jessie Henry?

Call me Jessie Bell or Jessie Hunt or Jessie Payne, but not Jessie Henry, that was never really my name.

It’s all over now, Jessie.

Two of the younger officers made a seat for her by crossing their arms and she held on to their shoulders as they carried her to her horse.

This is the special treatment, she said. Officers, this is surely the nicest arrest I’ve ever had.

The horse they had brought for her to ride was fitted with a sidesaddle. It was awkward even to look at and, more than being arrested, it was the thing that angered her the most.

Jack Brown held on to the balustrade.

Jessie raised her hand to him and smiled and said, Jack Brown.

Jessie, he called after her.

She tipped her hat and said, Jack Brown, long life.

Jack Brown gave more of a salute than a wave and then he tucked his hand under his armpit and he was disturbed by the force of his heart and the rate it was beating. He watched the constabulary charge off, and Jessie, riding between them, her hair whipping out in all directions. There were two men in front of her, one on either side and two behind her, all holding guns. How could she possibly escape?

She did not turn around for a final glance or a wave, but Jack Brown kept his eyes fixed on the back of her and watched her figure shrinking in the distance. He had an impulse to run after her, to track her, to follow her. But he knew it was time to leave that impulse behind.

Standing there, he remembered his first sight of her, sitting by the river, contemplating what? He did not know. She looked to him now, as she had looked to him then, like a shifting thing on the landscape.

Soon she would be gone completely.

He wondered if she had always been an illusion and what, of any of it, had actually been real. Once upon a time, he had held her, he had smelt her, he had buried his own face in her hair. With his own ears he had worn her silence, her laughter, her swearing, and with his own eyes he had seen her spit and ride and fall. She was real. He had prints and tracks and memories to prove it.

Fuck, Jessie, he said and a tear rolled down his face and he knew then the truth of it. She would never be what he wanted her to be for him. She was not his lover and she was not his wife and she would never be. All his dreams of the two of them riding off together like two elemental forces combined, the mystery of what they might do together if they actually chose each other, all of that folded in beside him, an untracked path.

Jack Brown did not hear Lay Ping opening the door or walking across the veranda to stand beside him. But he did feel her hand upon his back and from just the warmth of it, he thought he might dissolve.

Come, she said finally. Come and lay down with me.

It was still early morning and no one was about, and they entered the house as if the house were their own. He followed Lay Ping, followed the tail of her robe, the swing of her hips, the twists of her hair. And in her room he followed her lead and they undressed and stood in front of each other. Then he was aware that everything in the room was utterly still except for their bodies, which were quivering.

Jack Brown took hold of her hips and he kissed her shoulder and with his mouth he followed the trail of her tattoo down to the dip of her back. Then he knelt behind her; looking up, the view was as supple and miraculous as a mountain. Scattered above her arse were the tattoos of rocks, the god and a goddess and the word SORROW. Kneeling there, holding on to the bones of her hips, Jack Brown was grateful that he was a man and not a myth and that he was alive enough to feel the heat of the body in front of him.

The constabulary rode all day and they camped at night with my mother between them. The next morning they were up at first light as the fields folded around them, and they stopped only when one of the officers dropped his gun.

My mother was not lying then when she sai

d, I’ve an awful pain in my gut, Sergeant.

Keep riding, men, yelled back the lead sergeant.

If I could just relieve myself, she pleaded.

The lead sergeant kicked his horse.

Sergeant, I’d hate for there to be an accident on your lovely saddle and your lovely pony.

All right, stop! said the sergeant. Let the convict down.

But her feet are cuffed, said one of the officers. And she says she needs to relieve herself.

She’ll have to find some way, said the sergeant.

The two young officers helped her down.

Conceal yourself behind that tree, said the sergeant, pointing to the near distance. We don’t need to see you or any woman disgracing herself. But you must yell and you must keep on yelling.

I’m sorry, Sergeant, said my mother. This may take a while.

Be quick, woman, and get it over and done with and do not waste our time.

The police officers watched her as she jumped, her legs cuffed together, jumping all the way to the tree.

I’m here, she yelled.

That’s it. Keep on yelling, said the sergeant.

Behind the tree my mother yelled, I’m here, as she plunged a hand into the neck of her blouse and pulled out the key she had found in Barlow’s jacket. She opened the locks of the cuffs around her ankles easily and quietly, all the time yelling, I’m here. She yelled as she slipped off her skirt and dropped to the ground and she yelled as she dug her elbows into the dirt.

Then my mother scuttled out into the long grass, as any escaping creature would do, except she had a clear voice within her and she yelled, I’m here, I’m here. And then she was silent.

In the valley, sound travels and distance is difficult to judge. Voices echo and you may never find their true source.

When they did not hear her, the officers stepped tentatively towards the tree.

Jessie! they cried. Jessie, are you there?

But she was not. Only the cuffs were on the ground with the madam’s skirt.

The officers mounted their horses again and sought her in different directions. But north, south, east and west, they did not find her.

She was on her stomach, snaking through the long, dry grass.

JESSIE IS MY MOTHER.

Forward and back I have tracked her. I have heard her like a song. I caught her voice here and there, and when I finally pieced it together, distinguished it all from the din, I knew she was mine to hear. I tracked her and all that she loved and some she did not, to know my mother. And then, as I felt in my own heart a wish for her freedom, in one single and shimmering note I heard her. She said: I am here.

THE STORY BEHIND THE STORY

AS A TEENAGER growing up in Australia in the Hunter Valley, about one hundred fifty miles north and inland from Sydney, I heard about a wild woman who hid out in a mountain cave not far from where I lived.

There was nothing written down about her life then. I didn’t even know her name. And what I did know was all hearsay: she was a trick rider, horse rustler, wanted woman. Her story seemed to be made of air more than earth, like a fairy tale, and just like that it took hold of my imagination.

Apparently she had lived and roamed in the area in the early 1920s, but it felt truer to me that she was still out there in the mountains sleeping rough, eating weeds and scraping through the bush.

I thought about her every day.

Just as soon as I was old enough, I left the Hunter Valley and I forgot about her. I filled my mind with more immediate things—adventure, study, love. And each had a way of covering up her story. I came to it again only through dissatisfaction in what I was reading and seeing. I knew plenty of unlikely heroines in life, but they seemed to be missing from history and fiction.

In my twenties, I started teaching creative writing for a living. I often launched the workshops with an appeal to students to “tell the story you most need to tell.” Of course, this is easy enough to say but much less easy to do.

Around this time, along with another writer, I was invited to travel to isolated country areas, including the Hunter Valley, to run a series of writing workshops. It was a wonderful gig. Mostly, I saw it as a chance to be paid well and escape the bustle of Sydney. I had no inkling of how the trip would shape me.

We drove happily down into the Hunter Valley and then out along the dusty roads to the Widden Valley. In each place we felt the fullness of local hospitality. One of the venues was an old timber hall in the middle of a paddock with the mountain ranges in view. For generations the hall had been the community meeting place for weddings, wakes and christenings. You could actually see dance steps worn into the floor.

After I had spent two days there, working with students of all stripes and ages—an equine dentist, a mother, the mayor—one woman gave me the gift of a book. It was an amateur historian’s account of that wild woman who had lived in the mountain cave. But now she had a name. She was Jessie Hickman.

I drove back to Sydney with the queasiest feeling. In part, it was the strangeness of having forgotten about her, like forgetting a dear friend. And then this new and sudden sense of responsibility towards her or, more accurately, to her story. I hadn’t even reached the highway and already there was a strong argument forming in my head. This woman had a name, a birthplace. She was fact and I wrote fiction.

This argument continued for the four-hour drive back to Sydney and then went on for the next five years or so. Fact versus fiction. Even so, Jessie Hickman inspired enough daring in me to surreptitiously seek out prison records and social histories, all in the hope of finding more traces.

After years of her fantastical presence in my life, when I found Jessie’s prison mug shot, she became solid to me. There she was: “Jessie McIntyre alias Bell alias Payne” (not yet known as Hickman), “of eyes brown,” “of hair dark brown,” “special features: nil.” For me, her smudged eyes were the missing piece. Coal-dark, they were earth itself, expressing everything that took me a whole novel to say.

I copied this image of Jessie, took it home, framed it. I hung it above my desk—which, in hindsight, was a foolish thing to do. Her face is so intimidating. The way her jaw juts out challenges all that might be false or whimsical. I was stuttering beneath it. I wanted to get her story right, to give her a voice, to tell her story from her point of view. But what I was learning of her, no question, was that here was a woman of action, not words.

Since the book’s publication, some readers have asked me, “Why choose to tell the story through the dead and buried baby?”

The simplest answer is, I couldn’t tell Jessie’s story any other way.

For me, the child as narrator is that part of Jessie she had to bury because of the plain brutality of her life. Her softness had no place in the rough world where she found herself. So more than anything, that is what I wanted to give voice to, that is the story I needed to tell.

Recently, I went back to the Hunter Valley on a book tour. While I was there, I met an older woman who asked me how I knew that Jessie had given birth to a premature child who did not survive. I told her I didn’t know for sure, there was no record of it. Then I added, a little defensively, “Well, it is fiction, after all.”

The woman had no interest in my fact-versus-fiction debate. She began telling me her own story—how she’d lived her whole life at the foothills of the Widden Valley ranges where Jessie had roamed, how her father used to take her on long drives looking for lost sheep and cattle. One day he pulled up on the side of the road near a river and said, “This is where Jessie Hickman lost her child.”

I don’t know if the woman’s story is true. There is no way to know. It is hearsay, after all. And people do like to tell stories. But what I have learned, or rather, grown into, is a faith in fiction. Because no matter how far you take it, fiction always circles back. Somehow it always wants to tel

l the truth.

—Courtney Collins

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

FOR THEIR UNIQUE PART in the life of this book (in chronological order), heartfelt thanks to my agents Benython Oldfield and Sharon Galant of Zeitgeist Media Group, Jane Palfreyman, Clara Finlay, Ali Lavau, Juliette Ponce, Erika Abrams, Sam Redman, Clare Drysdale, Stéphanie Abou, Amy Einhorn, Liz Stein, Inés Planells, Silvia Querini, Ageeth Heising, Marianne Schönbach, Ilse Delaere, Maaike le Noble and Norbert Uzseka.

For their care and support, special thanks to Caroline Baum, Daniel Campbell, Kirsty Campbell, Siobhán Cantrill, Louise Cornegé, Alison Drinkwater, Angie Hart, Anna Helm, Fiona Kitchin, Lilith Lane, Gareth Liddiard, Kathryn Liddiard, Lisa Madden, Jeanmarie Morosin, Kate Richardson, Jackie Ruddock, Amanda Roff, Jasmin Tarasin, Jo Taylor and Meredith Turnbull.

And to my family—Collins, Diffley and Field combined, thanks and love always.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

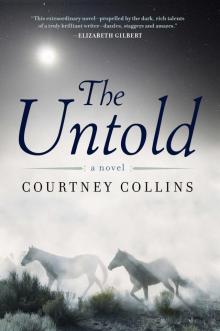

COURTNEY COLLINS grew up in the Hunter Valley in New South Wales, Australia. When she is not traveling, she lives on seventy acres next to the Goulburn River in regional Victoria, Australia. The Untold is her first novel, and she is currently at work on her second, The Walkman Mix.

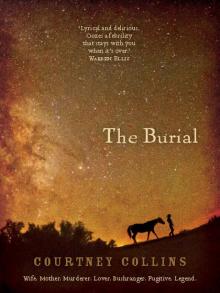

The Burial

The Burial AREA 69: An Alien Invasion Romance Novel

AREA 69: An Alien Invasion Romance Novel The Untold

The Untold